This is crazy-fascinating!

A new company claims they may be able to bring back the wooly mammoth by 2027.

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/14/1036884561/dna-resurrection-jurassic-park-woolly-mammoth

This is crazy-fascinating!

A new company claims they may be able to bring back the wooly mammoth by 2027.

https://www.npr.org/2021/09/14/1036884561/dna-resurrection-jurassic-park-woolly-mammoth

Another adventure in the ongoing saga,Tales of Covid. Despite all the perky reassurances that our initial Pfizer shots were still “highly” effective, whatever that means, Dear Husband and I were eager to get a third shot as soon as possible.

Breaking news Friday was that the Oregon Health Authority would follow the CDC’s Thursday booster recommendation for us 65+-ers as well as the immunocompromised and workers in potentially perilous industries.

Actually finding somewhere to do it was a bit more challenging. The first stop was a nearby RiteAid drugstore, where the apologetic youngster at the prescription drop-off told us they were waiting for the OR pharmacy board to also get on board so nothing was likely to happen any time soon.

Next stop: the Internet, to check availabilty through our local healthcare system. Although phone calls and attempting an online appointment proved futile, the walk-in urgent care clinic seemed poised to administer boosters, so off I went first thing Saturday morning while DH stayed behind to watch football and await my report. I expected long lines of eager seniors brandishing canes and face masks, but the clinic looked quite deserted.

I wasn’t optimistic, since the receptionist chirpily showed me a now-out-of-date notification that only mentioned the immunocomprised with an eight-month timeline for eligibility. But, to her credit, when I pointed out the smaller line reading “some people who received the Pfizer vaccine may get a booster six months after their second dose”, she allowed me to sign in. One of the few times that vagueness has been a benefit!

While waiting to be called back, I was happy to see two pairs of 20-somethings arriving for their second shots. The message is finally trickling down that the vaccine is a) effective and b) necessary if we’re ever going to beat this thing.

One quick jab, one sore arm, and several headaches later, I feel poised to rejoin the world with a bit less anxiety. DH, who received his booster Saturday afternoon, had more severe side effects — fatigue, soreness, headache, and feeling “flu-ish”– but is on the mend.

Wishing that those who spread misinformation and/or continue to cause harm to others by refusing to get vaccinated would be held accountable.

Samantha Wendell’s funeral will now be held at the church where she had planned to have her wedding. By Julie Mazziotta People Magazine

Samantha Wendell | CREDIT: BLAKE-LAMB FUNERAL HOME

A 29-year-old Kentucky woman who was fearful of getting vaccinated died of COVID-19 after missing her wedding while hospitalized with the virus.

Samantha Wendell had spent nearly the last two years planning her wedding to fiancé Austin Eskew, obsessing over every aspect of the big day, NBC News reported. The surgical technician from Grand Rivers had put off getting vaccinated, worried that her plans to have three or four kids with Eskew wouldn’t be possible after she heard false information from her co-workers that the shots led to infertility.

She “just kind of panicked,” Eskew, 29, said.

The Centers for Disease Control, OB-GYN groups and health experts have emphasized that the COVID-19 vaccines do not cause infertility and are entirely safe for hopeful or expecting moms. “It is just not true that getting the COVID-19 vaccine is associated with infertility in either males or females,” Dr. Wen, an emergency physician and public health professor at George Washington University, previously told PEOPLE.

RELATED: Unvaccinated Pregnant Nurse and Her Unborn Baby Die of COVID: ‘It’s Hard to Accept’

Wendell ended up changing her mind on getting vaccinated as the delta variant spread through the U.S., and decided that she and Eskew should get inoculated before their honeymoon in Mexico. She made appointments for them for the end of July, but after her bachelorette party a week prior, she started feeling sick and tested positive for COVID-19.

“She could not stop coughing,” Eskew, who got it too, said.

Neither of the couple had preexisting health conditions, and Eskew’s symptoms were mild. But Wendell continued to deteriorate and was hospitalized in August. She spent six weeks in the hospital, and five days before their planned wedding date of Aug. 21, Wendell was put on a ventilator. Just before, she asked doctors if she could get a COVID-19 vaccine.

“It wasn’t going to do any good at that point, obviously,” her mother, Jeaneen Wendell, said. “It just weighs heavy on my heart that this could have easily been avoided.”

by John Anderer (studyfinds.org)

ITHACA, N.Y. — The “catcall” is as outdated as it is cringeworthy. Interestingly, however, a new study finds human females aren’t the only ones who have to deal with unwanted advances. Researchers report that many female hummingbirds display the same bright colors as males — all to help avoid unwanted behaviors from males looking for a mate.

This research focused on white-necked Jacobin hummingbirds living in Panama. Over a quarter of studied females had coloring usually associated with male hummingbirds. Researchers say these colors keep doting males from harassing females with common behavior such as pecking or body slamming.

“One of the ‘aha moments’ of this study was when I realized that all of the juvenile females had showy colors,” says first study author Jay Falk, currently a postdoc at the University of Washington, in a media release. Mr. Falk led this research when he was a part of the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and Smithsonian Tropical Research Institute. “For birds that’s really unusual because you usually find that when the males and females are different the juveniles usually look like the adult females, not the adult males, and that’s true almost across the board for birds. It was unusual to find one where the juveniles looked like the males. So it was clear something was at play.”

Male white-necked Jacobin hummingbirds are known for their bright, distinctly flashy color patterns, usually characterized by beautiful blue head markings, and a bright white tail and stomach. Adult females, meanwhile, aren’t as colorful, usually displaying more muted tones of gray, green, and black that work much more efficiently as camouflage.

As children, even females display vibrant colors before seeing their markings grow more muted with time. However, among the juvenile females studied by researchers, around 20 percent retained their bright colors well into adulthood. As of today, study authors can’t say exactly how or why this occurs in some female hummingbirds. It may be genetic, environmental, or entirely up to choice. That being said, researchers do conclude that whatever the mechanism, the purpose is to help avoid aggressive male behavior and harassment during feeding and mating.

“Hummingbirds are such beloved animals by many people, but there are still mysteries that we haven’t noticed or studied,” Falk explains. “It’s cool that you don’t have to go to an obscure unknown bird to find interesting and revealing results. You can just look at a bird that everyone loves to watch in the first place.”

In an experiment, the research team placed stuffed hummingbirds nearby and watched as real hummingbirds interacted with the fakes. Sure enough, males primarily harassed the fake birds with muted color patterns, and left the others alone. Additionally, most females only have bright colors as children, which is of course not a time when mating is even possible.

In the future, study authors would like to use this work to help research how differences between males and females develop across other species.

The study is published in Current Biology.

Am I the only person who has managed to do laundry for decades without learning that occasional white spots or streaks on dark clothes are caused by too much undissolved detergent? Please don’t embarrass me by replying, “Well, duh, everyone knows that!”

Anyway, I know this now. And while I was emptying the lint trap today — today being laundry day around here — it occurred to me that we often accumulate little unwanted specks of debris in our psyches, too.

Mental “lint” accumulates when we’re exposed to too many little bits of negativity. It could come from the news. The jerk driver who cut you off. A chance remark by a nasty neighbor or co-worker. It could even be a self-deprecating thought that makes us doubt our own worth.

And, just like doing our laundry, we need to regularly empty our mind’s lint trap and start afresh. At least once a week.

WASHINGTON — Think it’s all downhill for your brain after you hit 50? Think again. Like a fine wine, some mental skills such as concentration and paying attention to detail, believe it or not, actually improve with age.

The exciting discovery could lead to better therapies for Alzheimer’s disease, say scientists.

“These results are amazing, and have important consequences for how we should view aging,” says senior investigator Michael Ullman, PhD, a professor in the Department of Neuroscience at Georgetown University and director of its Brain and Language Lab., in a statement.

The study of hundreds of older people found two key brain functions get better from our 50s onwards. They include attending to new information and focusing on what’s important in a given situation. They underlie memory, decision making and self control, and are even vital in navigation, maths, language and reading.

“People have widely assumed attention and executive functions decline with age, despite intriguing hints from some smaller-scale studies that raised questions about these assumptions, but the results from our large study indicate that critical elements of these abilities actually improve during aging, likely because we simply practice these skills throughout our life,” says Ullman. “This is all the more important because of the rapidly aging population, both in the U.S. and around the world.”

Ullman believes deliberately improving these abilities will help protect against brain decline.

Dementia cases worldwide are expected to triple to around 150 million by 2050. With no cure in sight, there is an increasing focus on lifestyle changes that reduce the risk.

For their study, the international team looked at three separate components of attention and executive function in 702 participants ages 58 to 98, when cognition often changes the most. The brain networks are involved in alerting, orienting and executive inhibition. Each has separate characteristics and relies on different regions, neurochemicals and genes, suggesting unique aging patterns. Alerting is characterized by a state of enhanced vigilance and preparedness in order to respond to incoming information. Orienting involves shifting brain resources to a particular location. The executive network shuts out distracting or conflicting information.

“We use all three processes constantly. For example, when you are driving a car, alerting is your increased preparedness when you approach an intersection. Orienting occurs when you shift your attention to an unexpected movement, such as a pedestrian,” explains first author Dr Joao Verissimo, of the University of Lisbon, “And executive function allows you to inhibit distractions such as birds or billboards so you can stay focused on driving.”

Remarkably, only alerting abilities were found to decline with age. In contrast, both orienting and executive inhibition actually got better. The latter two skills allow people to selectively attend to objects, and improve with lifelong practice, explain the researchers. The gains can be large enough to outweigh any underlying neural reductions.

In contrast, alerting may drop off because this basic state of vigilance and preparedness does not get better with implementation.

“Because of the relatively large number of participants, and because we ruled out numerous alternative explanations, the findings should be reliable and so may apply quite broadly,” says Dr Verissimo, “Moreover, because orienting and inhibitory skills underlie numerous behaviors, the results have wide ranging implications.”

“The findings not only change our view of how aging affects the mind, but may also lead to clinical improvements, including for patients with aging disorders such as Alzheimer’s disease.” adds Ullman.

The findings are published in the journal Nature Human Behavior.

South West News Service writer Mark Waghorn contributed to this report.

Jealousy is.

Money can fund philanthropy, the arts, technical innovation, beauty, medical breakthroughs, and many public services we take for granted.

Jealousy has a lot less to recommend it (though it might provoke healthy competition).

In our tiny neighborhood, jealousy has recently run amok. Sometimes expressed in the loathsome designations “up the hill” or “down the hill”, we’ve got an awful lot of neighbors (in both senses) obsessively focused on who has a better view, a nicer house, a prettier yard, or an apparently easier life.

Oh, this is seldom verbalized in any direct way. The jealousy is cloaked in righteous indignation: “Those damn so-and-so’s are breaking the rules again!” by allowing their dog to escape the yard and do its business “wherever it chooses”. The finger-pointers didn’t bothered to learn that said dog was dying of cancer and unable to control its bodily functions. (Dog died=problem solved=do move on, please.)

Then, there are false and oft-repeated claims that the committee responsible for managing the landscaper’s schedule spends the budget keeping the areas near the ocean looking good “for the benefit of the people who live down the hill”. Yet, these same folks are the first to grumble if their view becomes overgrown.

And finally, complaints about matters long since resolved, such as whether someone’s outdoor lighting is too bright. (Consider: #1 There are no street lamps in the community, #2 Ever thought about getting window shades?, #3 Maybe if you asked nicely?)

Sheesh. Have a nice glass of vitriol and (don’t) call me in the morning. I’ll be working on my next rant.

Confirming what we’ve all suspected. Had to share!

A study finds jerks online are jerks all or most of the time.

https://gizmodo.com/online-trolls-actually-just-assholes-all-the-time-stud-1847575210

This is a fascinating analysis of COVID’s two-month cycle, with the Delta variant following a similar pattern to the first outbreaks. (Apologies for formatting wonkiness — cutting and pasting NYT articles doesn’t always work well.)

A testing site in Auburndale, Fla., last month.Octavio Jones for The New York Times |

| Almost like clockwork |

| Has the Delta-fueled Covid-19 surge in the U.S. finally peaked? |

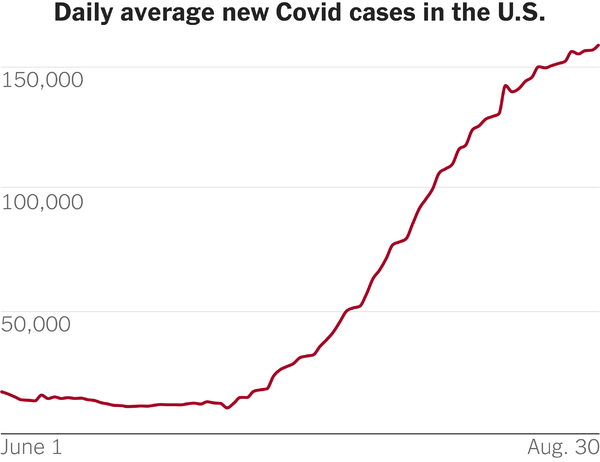

| The number of new daily U.S. cases has risen less over the past week than at any point since June, as you can see in this chart: |

The New York Times The New York Times |

| There is obviously no guarantee that the trend will continue. But there is one big reason to think that it may and that caseloads may even soon decline. |

| Since the pandemic began, Covid has often followed a regular — if mysterious — cycle. In one country after another, the number of new cases has often surged for roughly two months before starting to fall. The Delta variant, despite its intense contagiousness, has followed this pattern. |

| After Delta took hold last winter in India, caseloads there rose sharply for slightly more than two months before plummeting at a nearly identical rate. In Britain, caseloads rose for almost exactly two months before peaking in July. In Indonesia, Thailand, France, Spain and several other countries, the Delta surge also lasted somewhere between 1.5 and 2.5 months. |

* Between February and July 2021, depending on the country.The New York Times * Between February and July 2021, depending on the country.The New York Times |

| And in the U.S. states where Delta first caused caseloads to rise, the cycle already appears to be on its downside. Case numbers in Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, Mississippi and Missouri peaked in early or mid-August and have since been falling: |

The New York Times The New York Times |

| Two possible stories |

| We have asked experts about these two-month cycles, and they acknowledged that they could not explain it. “We still are really in the cave ages in terms of understanding how viruses emerge, how they spread, how they start and stop, why they do what they do,” Michael Osterholm, an epidemiologist at the University of Minnesota, said. |

| But two broad categories of explanation seem plausible, the experts say. |

| One involves the virus itself. Rather than spreading until it has reached every last person, perhaps it spreads in waves that happen to follow a similar timeline. How so? Some people may be especially susceptible to a variant like Delta, and once many of them have been exposed to it, the virus starts to recede — until a new variant causes the cycle to begin again (or until a population approaches herd immunity). |

| The second plausible explanation involves human behavior. People don’t circulate randomly through the world. They live in social clusters, Jennifer Nuzzo, a Johns Hopkins epidemiologist, points out. Perhaps the virus needs about two months to circulate through a typically sized cluster, infecting the most susceptible — and a new wave starts when people break out of their clusters, such as during a holiday. Alternately, people may follow cycles of taking more and then fewer Covid precautions, depending on their level of concern. |

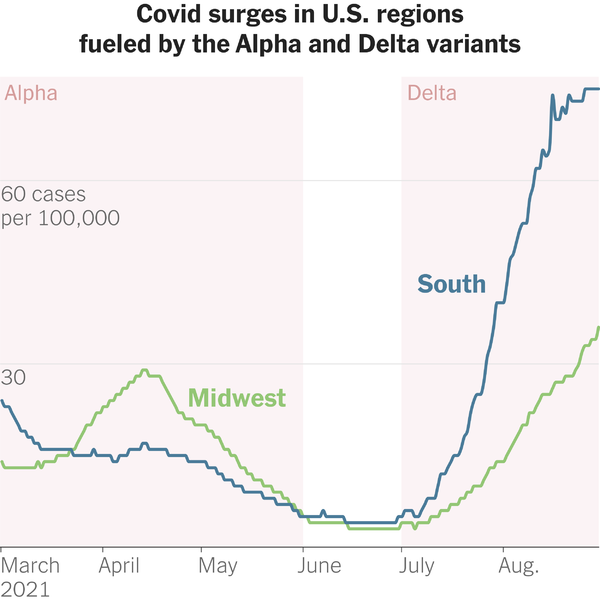

| Whatever the reasons, the two-month cycle predated Delta. It has repeated itself several times in the U.S., including both last year and early this year, with the Alpha variant, which was centered in the upper Midwest: |

| What now? |

The New York Times The New York Times |

| In a few countries, vaccination rates have apparently risen high enough to break Covid’s usual two-month cycle: The virus evidently cannot find enough new people to infect. In both Malta and Singapore, this summer’s surge lasted only about two weeks before receding. |

| We want to emphasize that cases are not guaranteed to decline in coming weeks. There have been plenty of exceptions to the two-month cycle around the world. In Brazil, caseloads have followed no evident pattern. In Britain, cases did decline about two months after the Delta peak — but only for a couple of weeks. Since early August, cases there have been rising again, with the end of behavior restrictions likely playing a role. (If you haven’t yet read this Times dispatch about Britain’s willingness to accept rising caseloads, we recommend it.) |

| In the U.S., the start of the school year could similarly spark outbreaks this month. The country will need to wait a few more weeks to know. In the meantime, one strategy continues to be more effective than any other in beating back the pandemic: “Vaccine, vaccine, vaccine,” as Osterholm says. Or as Nuzzo puts it, “Our top goal has to be first shots in arms.” |

| The vaccine is so powerful because it keeps deaths and hospitalizations rare even during surges in caseloads. In Britain, the recent death count has been less than one-tenth what it was in January. |

Your source for things you didn't know you needed to know

Tales of Mystery and the Supernatural

aka operasandcycling.com

Mit Wohnmobil und Kamera auf den Spuren der Natur

Tale of Net Cancer

Interesting Facts, History, Photos and Shop. Carre de Paris© 2012-2023 All Rights reserved

Whatever That May Be

Author and Anti-Bullying Advocate

Travel and Lifestyle Blog

Traveling to experience places not just visit them!

Rachel McAlpine writes, blogs, draws and podcasts here

Ramblings of a retiree in France

A personal blog that shares writing & positivity

For when France seems too far away. Shop for inspiring images of France and discover travel tips, packing advice, recipes, book reviews and more.

Raku pottery, vases, and gifts

Where shall we go today?

Random musings on style and substance

Life in islamic point of view

The Best in Home Decor and Gardening Tips and Advice