[edited from historyfacts.com]

Samhain (pronounced “sow-in”), the ancient Celtic festival that inspired many of our modern-day Halloween traditions, represents the end of the harvest season and the onset of winter. An Irish Gaelic word also used in Scottish Gaelic and Manx, “Samhain” translates to “summer’s end”. Traditionally celebrated on November 1, it marked the time when the harvest had been gathered and stored, cattle were moved to closer pastures, livestock were secured for the winter, and communities were hunkering down for the long, cold months ahead.

Samhain was also believed to be a time when the spirits of those who had died during the year traveled to the otherworld. People believed that during Samhain, the boundary between the living and the dead was at its thinnest, allowing the spirit world to interact with the human world. To protect themselves from restless or malevolent spirits, people would light fires, leave offerings for deceased loved ones, and wear disguises.

Today, much of what we know about Samhain is rooted in Irish mythology, making it difficult to discern truth from lore. But here are five things we do know about this ancient and mysterious holiday.

It Dates Back to the Iron Age

Observed by the ancient Celts across Ireland, Scotland, and the Isle of Man, Samhain dates back to the Iron Age, more than 2,000 years ago. The Celts divided the year into two halves, Samhain (the darkness) and Beltane (the light). Those two halves were further divided by Imbolc (a holiday marking the beginning of the spring season) and Lughnasadh (marking the beginning of the harvest season). These four cross-quarter days, as they were known, were celebrated with fire festivals and were among the eight sacred days in ancient Celtic tradition, along with the spring and fall equinoxes and summer and winter solstices, known as quarter days.

Some historians believe that Samhain, which fell on the day that corresponds to November 1 on the contemporary calendar, marked the beginning of the Celtic new year, while others argue there isn’t enough evidence to support that hypothesis. What we do know for certain is that elements of Samhain influenced the celebration of Halloween as we know it.

Samhain Came Before All Hallows’ Eve

Irish immigrants brought the traditions of Samhain to the United States in the 1800s, but the name “Halloween” traces back to influences of early Christianity as the church sought to incorporate pagan traditions into a Christian narrative in order to woo converts. In the eighth century, Pope Gregory III designated November 1 as All Saints’ Day to honor Christian martyrs and saints. By the 10th century, November 2 was recognized as All Souls’ Day, a time to remember the souls of the dead.

Over time, All Saints’ Day became known as All Hallows’ Day, and the evening before, called All Hallows’ Eve, eventually morphed into Halloween. Celebrated on the night of October 31, Halloween isn’t the same thing as Samhain, but the Celtic holiday inspired several traditions of our modern-day Halloween, including carving vegetables, dressing in costumes, and visiting homes to receive treats.

Fire Was Central to the Celebration

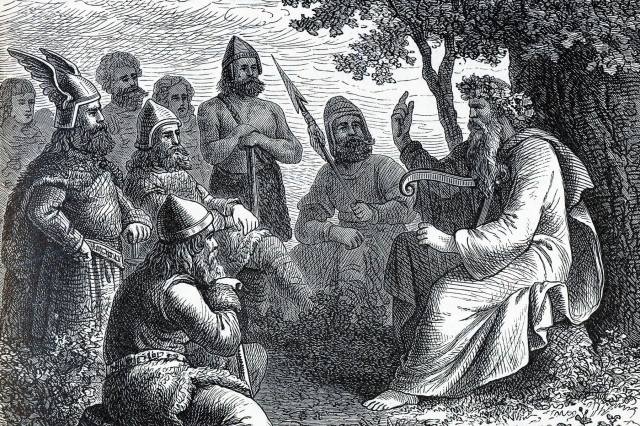

Marking the midpoint between the fall equinox and winter solstice, Samhain was the most important of the four fire festivals, coming as it did at the end of the harvest and the beginning of the colder, darker days ahead. The festival was observed over several days as a means of celebrating the harvest, appeasing the gods, honoring the dead, and warding off spirits.

Conflicting sources say that people’s hearth fires would either burn out from being left unattended during the gathering of the harvest or were deliberately extinguished at the start of the Samhain festival. In either case, after the harvest had been gathered, a large communal fire was lit by Celtic priests, known as druids. Sacrifices of crops and animals were made, and the animal bones were then tossed into the “bone-fire,” which is where we get the word “bonfire.” Celebrants would light torches from the bonfire to take back to their homes in order to relight their own hearth fires.

People Believed They Could Commune With Spirits

The Celts believed that Samhain was a time when the spirits of the dead could walk the world of the living, and that this temporary “thinning of the veil” between life and death meant it was possible to communicate with the deceased. A tradition known as a “dumb supper” involved setting a place at the head of the table to invite deceased ancestors to visit. The meal was served in absolute silence and celebrants avoided looking at the head of the table because they believed seeing the spirits would bring bad luck. After the supper, the untouched meal of the spirits was taken out and left in the woods.

Divination practices were also popular during Samhain because people believed the heightened spiritual energy of this liminal time was conducive to fortunetelling. Apples and nuts were used to predict the future and answer questions about the unknown. Some of these traditions later evolved into games, such as bobbing for apples.

Costumes and Carvings Were Meant To Deter Spirits

During the ancient festival of Samhain, people would wear masks, veils, and ghostly disguises to conceal their identity, confuse the spirits, and protect themselves from evil. Costumes were generally made from animal skins, and face coverings might have been an effort to impersonate dead ancestors. Children, meanwhile, would go from house to house showing off their disguises and singing or performing silly tricks in exchange for treats.

The Celts also created lanterns by carving faces into root vegetables that had been gathered during the harvest, including turnips, beets, and potatoes. These lanterns were illuminated with candles and placed in windows and outside of homes to ward off mischievous otherworldly visitors, including demons. This vegetable-carving tradition came to the U.S. with Irish and Scottish immigrants who discovered that pumpkins, which weren’t indigenous to Ireland, were well suited for carving.

So there you have it. Happy Halloween, everyone!

I now know far more about Halloween than I ever did Hi. Take care. Neil S.

LikeLiked by 1 person